The Seychelles are known as paradise on Earth – but even here, storm clouds are gathering.

As the ocean absorbs more heat and CO2 from the atmosphere, it warms up and becomes more acidic. That causes bleaching and destruction of sensitive coral reefs.

NGOs work to rebuild coral reefs

Rafaela Gameiro and Nora von Xylander lead coral restoration projects with a local NGO, the Marine Conservation Society Seychelles.

“We had two major mass-bleaching events,” says Rafaela. “One in 1998 and one in 2016, which caused the mortality of more than 90% of all the corals in the islands. When you dive you can see that most of the coral reef is dead – it’s almost like a coral cemetery.”

To save the reefs, the activists are building artificial nurseries, nurturing and then transplanting more resilient corals. Death of reefs can trigger a collapse of the whole marine ecosystem, undermining fisheries and eco-tourism – and further endangering the coastal areas.

“They are a barrier, basically, for the waves before hitting the land,” explains Nora. “So if coral reefs disappear, it would create big problems for islands like Seychelles in terms of coastal erosion, flooding, and the way that beaches look like.”

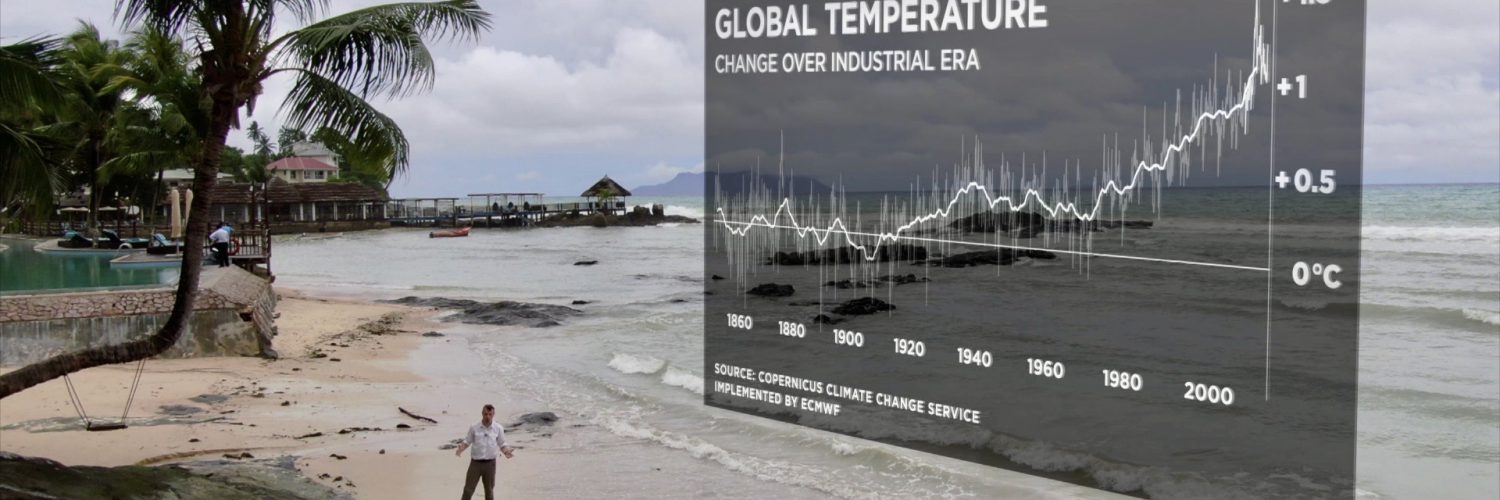

Coral bleaching is just one example of how ocean warming is hurting marine ecosystems and coastal communities around the world. The UN experts made it clear that global warming beyond 1.5°C will drastically alter the oceans, ice caps and glaciers. Scientists call for urgent action to reduce emissions and help those who are most vulnerable.

Climate change is upsetting the local economy

Storm surges, intense rains and coastal erosion pose existential risks to Small Island Developing States – where a third of the population lives near sea level. The EU has close relations with the Seychelles and is helping the country to reinforce its coastline.

“Here, coastal erosion means disappearance of the islands – that’s the reality,” says Vincent Degert, EU Ambassador to the Republic of Mauritius and the Republic of Seychelles.

“There are 90,000 people living here in the Seychelles. Their homes, their restaurants, their economic activity – everything is put at risk by climate change. So there is a genuine need to take action together.”

Growing number of tourists, mostly from Germany, France and Italy, come to visit the magnificent beaches and natural reserves of La Digue – Seychelles’ third most populated island. For some of them, the unusually early start of the rainy season is a disappointment. For local farmers like Jimmy Mellon, the risk is losing their harvest to flooding.

“The papayas don’t like water,” he says. “One-two days of flooding and they’re gone.”

At the only school on the island half, the students have been made to stay at home after the sewers flooded — it’s the second time it has happened over the past few years.

“We cannot close the school every now and then each time it rains, each time there’s flooding. So we need to find a solution for that, once and for all,” says Head Teacher Michel Madeleine.

EU funds shoreline management plan

Tourists and locals wade through flooded streets – as existing drainage systems cannot cope with increasingly heavy rains and growing real estate development.

“We need a good drainage system to properly evacuate the floodwater,” says the resident of La Digue Therese Payet. “That would be a great solution for us.”

The European Union allocated 3 million euros under the Global Climate Change Adaptation programme to help deal with the flood problems and prevent the salinification of La Digue’s agricultural fields.

“There will be projects to be implemented under the programme which the EU has committed itself to fund,” says Jean-Claude Labrosse, Principal Climate Adaptation officer, at the Seychelles Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change. “One will be of course the shoreline management plan; the other one is to increase our capacity to deal with flooding within the plateau and other areas; the other one is for the beach protection; and lastly, there will also be projects to mitigate saltwater intrusion further inland.”

“Today the world is like a global village – we cannot act in isolation. So if we are burning more fuel, if we are disposing more waste, it affects the seas, it affects the reefs, it affects the livelihood of people around the world.”