Crystal clear waters, white sands and kilometres of scattered islets, stretching as far as the eye can see; the Marshall Islands, a microstate in the Pacific Ocean, is a diver’s paradise, halfway between Australia and Hawaii.

The region’s tuna fishing industry, valued at €5.5 billion, is a vital economic resource for the countries and territories of Oceania.

However, climate change is a major threat to the Marshall Islands, shoals of tuna, particularly skipjack and yellowfin varieties, are projected to be migrating eastwards towards cooler open water due to rising sea temperatures.

According to a UN special report on the impact of climate change on the ocean, ten Pacific Island countries and territories could lose approximately €55.2 million a year in fishing fees and up to 15 per cent in revenue by 2050 due to these tuna migration patterns.

Why is tuna so important to the Marshall Islands?

If tuna stocks were to run out, this tiny nation and its Pacific neighbours would lose a vital natural resource and the key to their current economic development. The tuna industry has also created 25,000 jobs across the region, according to the region’s sustainable development body, the Pacific Community (SPC).

Approximately half of the world’s supply of tuna is caught in the western and central Pacific Ocean. The Majuro Atoll, where the capital of the Marshall Islands is located, is the busiest tuna transshipment port in the world.

“For us, of course, it’s an important livelihood, economic as well as our tradition and culture. It’s our backyard,” Glen Joseph, the director of the Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority, told Euronews.

What is the future of tuna and the Pacific people who rely on it?

The Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Tokelau signed the Nauru Agreement (PNA) in 1982 to harmonise the management of fisheries.

The PNA controls the world’s largest sustainable tuna purse seine fishery.

In addition, the Marshall Islands and eight neighbouring countries have pooled resources and collectively agreed on joint strategies to prevent overfishing through the Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC).

Fisheries in the western and central Pacific cover a fifth of the Earth’s surface and are subject to harvest control rules which ensure the stocks remain sustainable.

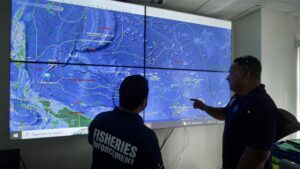

Local inspectors oversee the fishing and transshipment in the area. “We assign each vessel with an observer. So during transshipment, they can monitor the vessel’s activity and also verify tonnage on board” said Stephen Domenden, a Fisheries Boarding & Inspection Officer for the Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority (MIMRA).

“All purse seiners are covered 100 per cent. So when we board the vessel, we speak with the observer, we find out if everything is okay, all documents and everything on board is okay,” he added.

A monitoring centre in Majuro also keeps track of each vessel and has access to digitalised catch records, even before transshipment begins.

Tuna tagging is also vital for tracking the health of fisheries. The Pacific Community (SPC) has tagged some 500,000 tuna fish since 2006 to create the most comprehensive data set for tuna shoal management in the world.

“Back in history, there was no limit. You pay your access, you come and fish, whether you catch one fish or a thousand fish or a million fish, you go. But by imposing a limit, all of a sudden the onus is on the harvesters.

“They have to manage themselves within the quota that we’ve imposed. That raises the revenue, it supplements building roads, hospitals, schools, job creation and economic development for the islands,” Joseph told Euronews.

Fishing licenses account for half of the Marshall Islands’ revenue. The country’s neighbour, Kiribati, generates 70 per cent from fishing permits and Tokelau, 80 per cent.

However, transshipment adds little value to the land, which is why the Marshall Islands invest in new ventures. The Pan Pacific Foods tuna-filleting plant processes some of the frozen catch in Majuro before it is shipped to canning factories.

At the Marshall Islands Fishing Venture processing plant, the fish arrives chilled from the boats and is immediately graded based on size and quality. It is then filleted and air shipped the very same day to the US, Canada and Japan.

What is the EU doing to help?

The Marshall Islands are included in the FISH4ACP project, coordinated by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations with funding from the European Union and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The five-year programme improves every step of the tuna value chain, such as helping to build new cold storage facilities to expand tuna processing.

The sector aims to meet the standards required to enter the European market, compensating for the instability of fish prices in the region of origin. “The price is going down now, very cheap prices in all areas. So we need more markets, like the EU market,” Lin Huihe, the General Manager of the Marshall Islands Fishing Venture, told Euronews.

Although their CO2 emissions are low, Pacific Islanders are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and flooding. Furthermore, extreme weather events are increasingly frequent.

Life beneath the ocean’s surface is also affected. Coral reef bleaching damages marine ecosystems. The Marshall Islands are creating protected areas to help local species adapt and survive.

“Ten, twenty or fifty years in the future, I will not speak for that era, but we are trying hard to ensure that those people in that future can be able to live and thrive on their resources as Marshallese,” said Bryant J. Zebedy, the Marshall Islands Protected Areas Network Officer at MIMRA.