Ocean biodiversity is in dangerous decline. According to UNESCO, without significant change more than half of the world’s marine species may stand on the brink of extinction by the end of this century.

In Crete, marine biologists are seeing dramatic changes that are likely to spread across the Mediterranean.

In Crete, marine biologists are seeing dramatic changes that are likely to spread across the Mediterranean.

“The biodiversity, especially in shallow ecosystems, is changing fast. We get fewer species that we used to have, and we also have newcomers. We have new species coming, and new species establishing year after year,” says Thanos Dailianis, a Marine biologist at the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR) and the Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology and Aquaculture (IMBBC).

Increasingly barren seabeds

A protected clam species, the noble pen shell, have disappeared over the last two years, due to a fast-spreading disease combined with poaching.

Half of seaweed canopies, a habitat for other species, are gone, and the causes are not clear.

The biologists take notes, tracking these changes.

The biologists take notes, tracking these changes.

“For our work, the most important thing is to get in the water and observe how many species are there, so, if in 10 years time we see a different picture, we know what the previous picture was, and this is very important to understand what is happening,” says Dailianis.

The researchers collect data for several EU-funded projects aiming to protect and restore European marine ecosystems.

Underwater caves in Crete are rich with sponges and corals. But animals attached to the rocks can’t escape stressful conditions.

Observing their health, scientists write a “clinical record” of the sea communities.

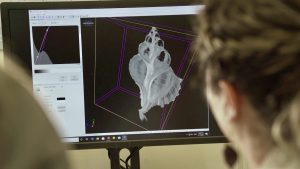

The images taken underwater are analysed at the Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology and Aquaculture.

The images taken underwater are analysed at the Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology and Aquaculture.

Researchers use special software to trace and classify the species.

“We take photographs in such a way that we can later quantify the surface cover of the organisms,” says Vasilis Gerovasileiou, Benthic ecologist, HCMR-IMBBC

“So our aim is to be able to revisit the caves in the future and see if there are changes in the benthic communities.”

“We have some historical evidence which is completely lacking in other parts of the world. So by using the Mediterranean Sea with all these changes due to human activities, due to tourism, due to increasing numbers of non-indigenous species, we can use it as a good example in order to understand what is happening in other parts of the world,” explains Gerovasileiou.

Some samples are collected for genetic analysis at the CretAquarium laboratory, which analyses whether the species are thriving or stressed, and reveals the organisms that are too small to see.

These European studies will help us better understand the causes of the biodiversity decline, ranging from pollution and overexploitation of marine resources to global warming.

Warming of the oceans

One of the experiments in their research tanks simulates long-term climate change, demonstrating how warmer and more acidic water affects sea snails.

“The experiment we’re doing here has to do with growth: we want to see feeding behaviour of the animal, the reproduction behaviour, we want to see also the interaction between prey and predator — how this will be influenced by the different seawater conditions,” says Panos Grigoriou, Marine biologist, CretAquarium.

“The experiment we’re doing here has to do with growth: we want to see feeding behaviour of the animal, the reproduction behaviour, we want to see also the interaction between prey and predator — how this will be influenced by the different seawater conditions,” says Panos Grigoriou, Marine biologist, CretAquarium.

If the concentration of atmospheric Carbin Dioxide continues to increase, the ocean will become more acidic and corrosive to the shells of many marine organisms.

“Climate change is very important as a factor affecting biodiversity, because if one species is affected, the whole balance will change. What we have here is an experiment for one animal, but this is just a baseline for knowledge for all the marine animals,” says Eva Chatzinikolaou, Marine biologist, HCMR-IMBBC.

The acidified conditions make shells thinner and more fragile which is dangerous for sea snails who can become easier prey for predators as the climate keeps changing.

Researchers use micro-computed tomography to visualise and accurately measure these effects.

Researchers use micro-computed tomography to visualise and accurately measure these effects.

“This specimen is in low-Ph conditions, and you can see that there are transparent areas, so we can see that we have less dense structures here. Climate change is increasing rapidly, so maybe the animals don’t have the evolution time to adapt to this new conditions, so maybe we’ll have massive mortalities,” says Niki Keklikoglou, Marine biologist, HCMR-IMBBC.

How ports affect marine biodiversity

“Ports act like a gateway for new species. New species attach to the hull of the boat, and those boats can spread those species to new places,” says Giorgos Chatzigeorgiou, Benthic ecologist, HCMR-IMBBC

“And when they establish in the new place, they compete with the native species. And this is a problem.”

With no local predators, populations of so-called alien species can explode in numbers, displacing indigenous fauna.

With no local predators, populations of so-called alien species can explode in numbers, displacing indigenous fauna.

To monitor this and other problems, researchers use stacks of special plates deployed in 20 locations around Europe.

After the stacks get colonised by small marine species over several months, researchers analyse them using genetic sequencing and other modern methods.

Samples collected in Crete can help other European researchers as well.

Pedro Vieira is a Marine biologist from the University of Minho. He is studying a particular worm, threatened in some parts of Portugal.

“Some habitats of this species are disappearing, so this species can disappear. Of course, they are important to monitor, because they can provide food for fish, for other animals, so the ecosystem can in theory collapse because of this.”

Light pollution

Even light pollution from the coasts might be harming small marine animals.

To investigate this, researchers deploy special traps that attract species most affected by increasingly omnipresent electric lamps.

To investigate this, researchers deploy special traps that attract species most affected by increasingly omnipresent electric lamps.

“The feeding behaviour of the animals could change and the relationships between the species, their interactions, could be changed because we affect the normal diurnal or nocturnal behaviour,” says Niki Keklikoglou, Marine biologist, HCMR-IMBBC.

“We want to protect the sea, we need to protect it because this way we protect ourselves. I think it’s very important for every biologist, and for every human.”